Four+ years into working and reworking a book that’s changed its name, its purpose, and its structure more times than I like to count, I’ve recently been startled to find the same words showing up in the two different and ostensibly dissimilar life events that have survived the manuscript’s constant dismantling and reconstruction. Besieged by a maelstrom of emotions during my three years in Abu Dhabi, I found myself confronting a spectrum of issues. These ranged from loss of control, anxiety, and threats to my ego — to the more enlightened emotions that gathered and grew the longer I was there: humility, honesty, release, acceptance, resilience, and love. Only recently has it dawned on me that in the two years of overwhelming sadness and grief that followed Philip and Winnie’s dying and deaths, I found myself again facing these same struggles and using these same words.

How can that be?

How can a crazy, stressful, cross-cultural experience be equated with the never-adequately described emotions of grief and grieving? Is it that grief is a foreign country to the heart?

Is Culture Shock—that upending experience of befuddlement and fear felt in a new country, of needing to find one’s footing in the face of customs, languages, and terrain that make little sense to us—somehow, and oddly, like what we experience when we are bereaved? In other words, how is the way we must adjust and adapt to life in a foreign country similar to the way grief takes us to a new inner land and requires of us a major transition? Neuroscientist and psychologist Mary-Frances O’Connor, who has investigated the impact of grief on the brain, suggests that the brain in grief is almost like a separate country, and as grieving progresses, it struggles to discover its new homeland. The impact of grief on the brain, I am finding, is akin to the impact of Culture Shock: both bring disorientation and anxiety because everything is so exhaustingly different from what we’ve known previously. O’Connor teaches me that falling in love with Philip decades earlier and being in love for nearly forty years created, over time, deeply encoded pathways in my brain. As such, in neuroscience-speak, the loss of this person required new encoding of new information. My brain had to establish new neural pathways in order for me to grow slowly into accepting his permanent absence. But before that could happen, while my brain was not yet readjusted, I struggled. My irrational self and my not-yet-adjusted brain believed Philip was still here, still somewhere–just temporarily away. It was this disconnect in the early months after his death that led to the yearning O’Connor speaks of as the hard but natural emotion that comes before we can make the painful transition into a new reality (a new country). In Abu Dhabi, I yearned for what was familiar. In grief, I ached for the presence of my husband and then my mother, who were no longer with me. This yearning in grief threw me into a limbo state, which was not unlike how I often felt in Abu Dhabi, a limbo land. Thinking about this now (and with the help afforded by O’Connor’s important work), the unanticipated similarity between the heartache of grief and my struggles in Abu Dhabi emerges ever more clearly.

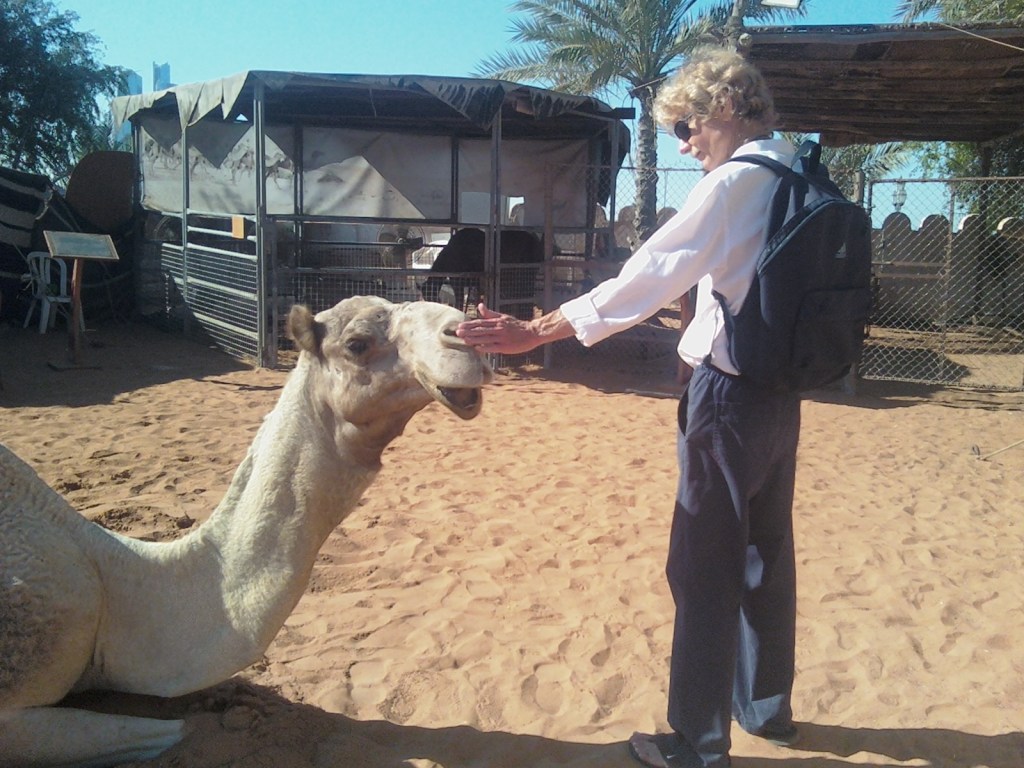

In Abu Dhabi, I was presented with daily obstacles that challenged my personality and customary ways of being. Interwoven amongst all these obstacles was the challenge to my sense of control. The girls, first and foremost, undermined my illusion of being in control. They didn’t ‘do college’ according to my expectations. They didn’t communicate or, in fact, live in ways that were familiar or comfortable for me. The college, too, wasn’t run like any college I’d attended as a student or worked at as a Counselor or an Instructor. Working in an unfamiliar place that itself seemed out of control – with changes in policy and practice handed down every other day – kept me off-balance for three long years. And then there was the city. It, too, was like none I’d known. On the ground, it was a chaotic, frenetic jumble that operated seemingly without rules. This itself was paradoxical in a land where so much of one’s life was heavily prescribed and regulated. But then Abu Dhabi was a place of paradoxes and inconsistencies. It was liberal and conservative, modern and medieval. In Abu Dhabi, Philip and I navigated a world that looked like a modern city but felt and even smelled utterly foreign. An ancient, nomadic, tribal energy vibrated beneath the high-rise buildings and modern shopping malls. We lived as strangers in a strange land, attempting to puzzle our way into this challenge to our need for control, a need we hadn’t been aware of until control was largely taken away.

In grief, loss of control was an enormous issue, as well. The world as I’d known it had changed without my consent. The two people I most relied upon were suddenly absent … again without my agreement. The rituals I’d cherished and shared with Philip lost meaning. My daily tasks, now faced alone, felt strange and wrong; a trip to the supermarket or food co-op created anxiety. The loss of my weekly walking and talking phone calls with Winnie left another hole in my life. Conversations with both Philip and Winnie were now held in my head. Of course, I felt out of control.

In Abu Dhabi, constant threats to my ego and identity followed on the heels of the loss of control. At the college, the teacher I’d been for most of my professional life could not recognize the teacher who struggled daily with the girls. And, no surprise, this evoked insecurity and fear. My ways of teaching weren’t working; my long-honed skills were suddenly all wrong. What was I going to do if I couldn’t bring a classroom together? If my style of teaching had ceased to be effective? What if I’d lost my competence? I’d certainly lost my confidence.

These obstacles and the uneasiness they evoked tied me in knots. To untangle those knots and survive Abu Dhabi, I was compelled to wave the white flag. I had to let go and release many of my preferences, expectations, and much of what I thought I knew about myself. But letting go is never easy. It creates its own angst. I would live in a similar space again ten years later as I navigated the waters of grief.

When I found myself widowed, I had a new box to tick on all the forms I’d been using for decades. How would I know myself when I was no longer half of the partnership that had defined my life for 37 years? What would I do with all the love I still had to give? Who would I look to for nurturance when I no longer had a mother? How does a daughter know herself when she becomes a motherless child? Who would I turn to when those people I shared with in times of sorrow and joy were permanently absent? Discomfort related to ego and identity became part of my newly bereaved existence I had not chosen and did not want.

The flip side of the coin holds words (and emotions) representing the strengths and resilience needed to move into and through the unfamiliarity of an uncomfortable cross-cultural experience and that of loss and grief. Two of those words are ‘honesty’ and ‘humility.’ The honesty to admit just how threatened I was came first. At the college, I reluctantly recognized the need to turn to colleagues for help; this was something I’d rarely done. Humility replaced an inflated sense of self. But what do I know? became a regular refrain at the end of my conversations. Professionally, up until Abu Dhabi, I’d felt respected, accepted, and admired; suddenly, I felt anything but. Honesty and humility were also required when my need for help became undeniable after Philip died. I found my way to a grief counselor. Relief flooded my heart when I found a safe person to whom I could openly and honestly express my pain and the uncertainty and disorientation of not knowing who I was anymore. I hadn’t been fully aware of how much I valued self-sufficiency until, suddenly, I’d been felled. For months, as I faced each new situation that had to face alone for the first time, I felt anything but self-sufficient. I felt unsteady on my feet and utterly vulnerable.

My saving grace in both situations came with inculcating the understanding and practice of release and surrender. The more resistance the girls offered, I (grudgingly) realized I was going to have to release my need to be in control. Each time I was disappointed because my expectations hadn’t been met, I learned (painfully) to let go of having things my way. Similarly, after the crushing pain of facing Philip’s death, after months of foot-stomping refusal and the unrelenting yearning for his return, I slowly surrendered; I reluctantly acquiesced to his absence. Not by choice. Not happily. But I am reminded of what a psychic told me 33 years earlier when I could not stop longing for the dog that died in 1978. She said the most loving thing I could do for him was to put my needs aside and set him free. Otherwise, in his love for me, his spirit would continue to be torn between wanting to stay nearby to comfort me versus his need to travel on, to be spiritually free. In 2016, I was telling myself this story again, but now it was Philip’s spirit I had to surrender. If I loved him, I had to release him.

Ultimately, what these two life-changing experiences keep teaching me is how to fall down and get up again. Resilience is a word I have come to honor. When we are knocked around or knocked down, there are any number of possible responses: I choose to get back up.

But I try to go one step further. I seek meaning in the ongoing struggle. To let the challenges and tests be my teachers. Such can only come with the acceptance of what is. Poet/philosopher Mark Nepo refers to this as an “Inner Curriculum.” He says the Inner Curriculum “…is working with what we’re given while staying close to what we love.…” Mary-Frances O’Connor writes of acceptance as the necessary act of allowing every emotion that arises simply to arise. Not to try to overcome or change or even find meaning in sorrow. Just to accept that it is. Acceptance is also identified as the final stage of Culture Shock. In Abu Dhabi, acceptance provided relief, as did time, experience, and surrender. Philip and I moved toward accepting Abu Dhabi as it was. We did not grow to love our life there, but by accepting it, we were better able to shift into more receptive curiosity, humor, and openness. And—amazing grace—I learned (at the age of 60, but better late than never) that I could tolerate and survive what I did not like. I could even grow into a fuller version of myself.

I am a perennial student who, in Abu Dhabi and in grief, had lessons to learn about control, anxiety, and ego. With humility, acceptance, and love, I learned to cope in Abu Dhabi, to cope and to grow. Thinking of those hard lessons learned under a Middle Eastern sun and recognizing the oddly similar lessons that confronted me years later when Philip and then Winnie died, it occurs to me that we rarely see how one chapter in our life may be preparing us for another. If we could understand this (and assume it!), we might better face and value the challenges that arise. We might meet the present moment with openheartedness and hence, achieve receptivity, even in the face of pain. We might surrender to each obstacle that comes our way, honoring a tiny inner voice that has accrued the wisdom to whisper, Wake up. Pay attention. You might need this in another, even more challenging situation to come.

With this awareness at the forefront of my consciousness, I feel the immensity of the gift Abu Dhabi was to me. It gave me the strength to live through grief, and who knows how the combination of Abu Dhabi and grief will help me in the future.

What is clear to me at this time is that a reflective and consciously lived life best proceeds with open-handed and accepting resilience, with honoring the challenges and embracing the love for all one has lost … and for all the love one has yet to live.

P.S. This piece is excerpted from the book-to-be. I’d love to hear your responses and thoughts. Would you read a book like this?

I post this on Philip’s birthday with infinite love and gratitude.

Discover more from Joan Heiman

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This is so beautifully written. And what you write about is thought-provoking and insightful. I look forward to this book!

LikeLike

Thanks so much for reading and responding so generously. With love.

LikeLike

Thank you. You were my ‘first responder’ this morning! Each time I send one of these posts out, I hesitate before ‘sending.’ How will I be received? Will I reach or touch someone? Does what I have to say warrant a post? So many questions (mostly and sadly informed by self-doubt and insecurity). And then responses start to come in, and people resonate and appreciate one thing or another that I’ve shared. I am so grateful … and gratified.

LikeLike

Joan – I enjoyed reading this excerpt from your upcoming book. Of course I’d be interested in your new book. I can’t express myself in words like you, similar to you not willing or able to handle finance like I do. I did grieve when Winnie and Sid died, but have found that grief dissipated to more a remembrance of them. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t think of them, but not in a sad way but generally happy times or at least, what would they say or think.

You keep writing and I’ll keep following the stock market. ❤️😘😍😊

Love

David

LikeLike

It’s a deal!

Thanks for reading and responding so kindly. With love.

LikeLike

This excerpt definitely draws me into knowing more. It’s introspective and asks good questions. I kept reading on because your writing teaches me things.Things like organizing

my emotions and figuring out the links from one life experience to another. You always write so profoundly good that I’m mesmerized to keep reading on. Here’s to the blessed memories of your Mother, Winnie, and your dearest Philip. Thank you for writing and writing. I learn do much about you and life from your thought’s pen.🩷

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind words. I have long been intrigued by what you rightly call “the links from one life experience to another.” And now, I feel that these links are also roads that we travel with stopping points along our ways. And … how wondrous to see that one experience teaches and prepares us for the next … and that one … for the next. The journey is long and purposeful. And full of love and awe.

LikeLike

Joan, I so resonate with your comparison of the grief experience with that of culture shock. As you know after Roy died I also felt I was a stranger living in a strange land. And stranger still to be having that experience without changing home or community. Your reflections on your experiences help me to see my own grief from a more expansive place.

LikeLike

Your response, as well as that of others, is so encouraging. Amidst all the doubts and questioning about whether I have anything worth sharing, I carry the hope that some of my message may provide support and even the healing that comes with feeling heard or understood. Thank you.

LikeLike

Phillipp and I read this together, then had no

Chance to respond but will tomorrow !

<

div>With love and memories

LikeLike

Thanks to both of you for reading it. Love.

LikeLike

Joan, Thanks for sharing this. Of course I would read a book like this! I’ve long been a fan of your wriiting, as you know, and I appreciate your story with its candor, observations and insights. Good luck navigating the publishing process. I suspect you’re getting to be a pro at that as well as the writing. I’ll look forward to reading the entire book! Please keep me posted! Liam

LikeLike

Thanks, Liam, for reading and responding. A pro? Umm … nope.

LikeLike